Looking for a Home

My parents, Joan and John Gill arrived in Miami in 1951. Northern beatniks, they drove south in an old woody station wagon, mom in her standard jeans and tee shirt, my father newly hired to a tenure track position teaching engineering at the University of Miami. They temporarily moved into a place near US-1 in Coral Gables where my brother Robin was born that same year. On the lookout for a home, mom spotted an old listing for a rental property on the Matheson Estate on Key Biscayne. She was immediately hooked by the South Seas image, “an ocean-side cottage nestled among coconut groves.” With sketchy directions, she found the causeway, reached Key Biscayne, located the coconut plantation, took a peak at the cottage, got the landlord Hardy Matheson’s phone number and rented the place, all in one afternoon. Always up for an adventure, dad was thrilled at her find.

Her Love for Writing

They moved onto the island weeks later, soon followed by our more-black-than-white Dalmatian, Lucky. My sister Susan was born in ’53, and I followed 13 months later in ’54. Mom stayed busy with us and her writing, often carrying her typewriter and escaping to the beach where she sat in our dingy, Bloody Awk, and worked on her novels in the years before she entered the magazine industry. Dad’s teaching and passion for experimental design, including hydrofoil advancement and adapting gas turbine engines for ocean racing, reinforced their decision to have moved to the tropics.

Along the Plantation

Six other families lived along the plantation’s gravel roads: Mackfield (Mac) and Gussy Mortimer and their nephew, Richard Neally; David Dean; Mr. and Mrs. Sheldon; Danny Paul and John Bates; Lloyd Jordon and his family; and the Pearsons. To the west of our house, just past the swamp and the large ficus tree, was the former commissary, which had recently been transformed into Little Island Playhouse, the nursery and kindergarten for the island. We did not have far to walk for those first couple of years. When St. Christopher’s first formed, we went to church in the kindergarten classroom until the congregation could move to the old Bahamian worker’s dormitory up the road. In its specially renovated and redesigned site, the church officially opened with Father Maholm as the Vicar. Further west was the big barn, still in use by Mac and David in the caretaking of the plantation, and for a time by Mrs. Revere as a stable for her horses. One day, Mac took us up the creaky ladders to the top floor and pointed up to the spot where he had clung for life to the rafters as the waters’ rose and the storm surge covered the island during the hurricane of 1926.

Days on the Beach

To the east of us, just past the only paved road on the plantation, aka The Asphalt Road, was the beach. Except for periodic remnants of the old jetties sentineling into the ocean, no other structures were visible from our beach along the length of the island. Many days we would not even see other people, some days they appeared as small groups of far away dots where the Key Biscayne Hotel, the Beach Club, Silver Sands and Crandon Park were set back from the dunes. We spent days on end at the beach, learning to swim before we could walk. For shade, we—first mom and dad and then all of us as we grew older—built lean-tos from found wood and fronds, tied with railroad vine. We seined along the shore, caught abundance of fish, often cooking on the beach in fire pits fueled by driftwood. Late night family-swims in the bioluminescent water are a favorite memory.

Family Trip

Another is an epic family trip, when I was about 6, walking south the length of the island, leaving the sounds of the palms, swinging between my parents hands past the densely whispered songs of the Australian pine forest to the deserted lighthouse, then round the Cape along the seawall that circled No Name—where Lucky fell in and was barely rescued from drowning by the lone boater in the harbor. To cross Pines Canal we built a raft from flotsam to help support us across the current, then dragged ourselves the rest of the way through the mangroves to the road, arriving burnt, bedraggled and parched at the Alspach’s house on Mashta, our home-away-from home.

The Island’s Population

In the late 50s, early 60s, as the island’s population and popularity grew, to our displeasure more people arrived. Along our section of beach, us kids built numerous people traps, small foot-sized holes filled with nettle, sandspurs, man-o-war, carefully camouflaged under sea oat cross-stems and Sargasso weed. We would lie in wait, concealed by dunes, or simply play nonchalantly along the shore. Our best catch was one of VP Nixon’s Secret Service agents. To any one else we may have trapped, my apologies.

About this same time period, my parents had a 28’ sharpie built by boat designers Wirth and William Munroe, the Commodore’s son and grandson respectively, who had also designed and built the Bloody Awk. The sharpie sat on a trailer in our side yard for a year as they finished out the interior and rigging. When it was time for launching, Mac brought over the plantation tractor and hauled it through to the back road, David following in the truck, then over the dunes and out to the beach—with much fanfare, yelling and chaos among all the adults trying to do it safely. Once afloat, she was christened with a bottle of ale across the stern stem carving that mom had done to signify her name, the Ibis. We kept the Ibis tucked away in Hurricane Harbor, tied up in the mangroves on the edge of an empty lot. With a crank-up centerboard, a backup 5-horse Seagull engine that clamped to the sheer rail, and a draw of just 11” with the centerboard up, we could traverse most shoal waters and island inlets in the area with little concern for running aground. We sailed throughout Biscayne Bay most weekends, with longer trips to the Keys, Florida Bay and the Everglades.

One Evening

One evening during a post-dinner family football game in the back side yard, we stumbled upon a tiny living something, so newly born it took us a bit to realize it was a raccoon. The mother was nowhere in sight so we carefully cradled the baby into our house. Mom learned to feed her with an eyedropper, then a doll’s baby bottle, then a child’s, with us kids never wanting to leave her side. She slowly grew into her name: Hurtsel Racketty Mascarado Gill. She was the love of our lives and Lucky became her best friend and champion, protecting her from any dog that came on the plantation to do her harm. When Freckles the beagle was added to our menagerie—which included box and snapping turtles; Margaroo the goose (briefly); ribbon, rat, indigo and garter snakes; B-flat the cat; Hamy Hampster 1–3 and Petie Parakeet 1 and 2—it was only possible because he had become Hurtsel’s wrestling buddy after Lucky’s arthritis had worsened.

Our Little Home

We loved where we lived, our little tiny home, built for a plantation worker in 1917 of Dade county pine, lathe and plaster. Raised on concrete stilts, air-conditioned under and through by direct ocean breeze only, shaded by Pongam, Australian pine, oleander, date and coconut palms, 700 square feet of living space set in 80 acres of paradise. We grew up feeling direct kinship with Robinson Caruso, Tarzan, and The Swiss Family Robinson.

A Gift to Us

To paraphrase from Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, “What good are forty freedoms without wild country to be young in?” Our parents’ gift to us, in their wisdom and love of nature, in their understanding of freedoms wildness, was life on Key Biscayne. We hated leaving the island, but in 1965 when the plantation went up for sale, we moved to the mainland, then on to Texas and New York before coming full circle back to Miami and a reconfigured family.

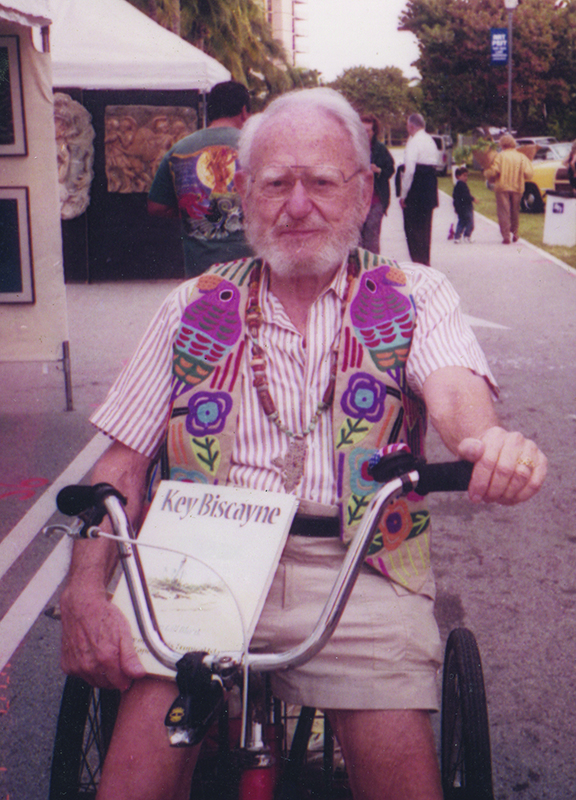

When my mom and stepdad, Harvey Blank, were married in 1975, it was with the ocean as backdrop in the living room of their new home in Mar Azul. For my mom, returning to the Key was to once again live where her heart had always been. And for Harvey—a world-renowned dermatologist, virologist, naturalist and Eagle Scout, who had also first moved to Miami in the 50s to accept a position at UM—to learn the island through mom’s eyes was a journey he loved and celebrated. Over a ten-year period, they traveled far and wide to places, archives, attics, libraries, private homes and collections to uncover and discover the depth of Key Biscayne’s history for her seminal book in 1994, Key Biscayne, and for creating the Key Biscayne Heritage Trail in 1996. Her writing throughout the years, whether for grants, articles or lectures has always combined history and the environment as foundational concepts of stewardship and islandhood. Mom, whose knowledge about this little barrier island’s history is a legacy unto itself, turns 90 in 2018. A Buffalo gal who fled the winters, raised her kids with a love of the tropics, still walks the beach each day.