Key Biscayne Historical and Heritage Society

The Cape Florida Lighthouse

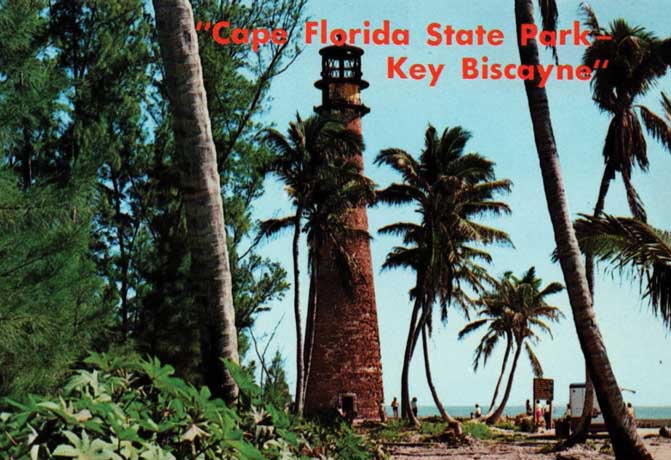

Of all the non-native historical iconography associated with Key Biscayne, the Cape Florida Lighthouse is the single most iconic. Although for a long time the functioning lighthouse has been largely inconsequential as an aid to navigation, the lighthouse image is omnipresent—from the Official Seal of the Village of Key Biscayne to tee-shirt logos, golf cart decals and branding materials of various sorts.

Whatever the marginal significance today of the light-beam itself, this looming presence still serves as a guide, marking our place historically and geographically as a gateway for commercial shipping so dangerously close to the shoals and shallows that spawned the area’s first European immigrant industry—shipwreck salvaging.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the first lighting of the Cape Florida Light. It may be that mariners always found illumination guidance around the tip of Cape Florida, where indigenous Tequestas or Miccosukees, or transitory pirates, or opportunistic wreckers, would light their campfires. Campfires were likely common, but hardly adequate to aid navigation around the treacherous Florida Reef, a constant danger to shipping from Key Biscayne to the Florida Keys. As settlements grew in Florida, and Key West became a commercial and territorial government center, shipping in our vicinity boomed. As did shipwrecks. And salvage operations.

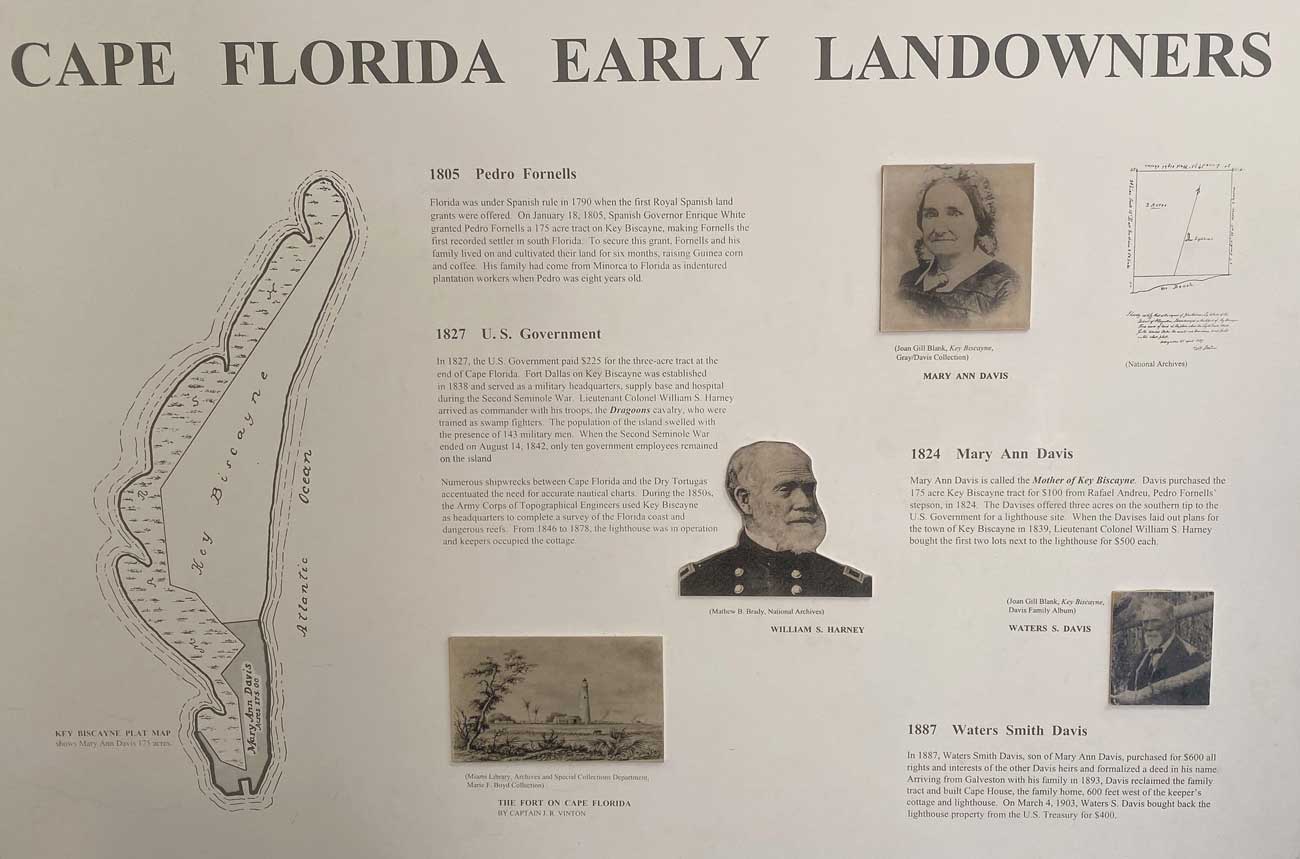

The lighthouse story begins in 1822, one year after Florida passed from a Spanish colony to a U.S. territory. That year, the U.S. Congress appropriated $8,000 to build a lighthouse. More appropriations soon followed, and in 1824 the federal government acquired a three-acre tract at the southern end of “Key Buskin”. A 26 year old Boston brickmason, Samuel B. Lincoln, was engaged to build three lighthouses, one at Cape Florida. Mr. Lincoln unfortunately never had the chance to apply his tradecraft in service of Florida infrastructure. He was lost at sea en route to St. Augustine; a casualty of a September 1824 hurricane. His older brother took over the job.

The design specifications called for a sixty-five foot solid brick structure, five feet thick at the bottom, tapering to two feet at the top. The job included a handsomely designed two-story brick lightkeeper’s cottage adjacent to the tower. One Noah Humphreys from Hingham Mass. was hired to oversee the project and certify as to its proper completion. Early in 1825 a large cargo of brick landed on Key Biscayne, along with building equipment and a skilled workforce. For a structure requiring careful measurements and precise assembly, construction proceeded rapidly.

John Dubose, a former Navy captain, customs inspector and interesting historical figure, was appointed as lightkeeper. A Mr. Waters Smith, the first mayor of St. Augustine and territorial marshal of the district from the St. Johns River to Cape Florida, recommended Dubose as a “gentleman of intelligence with abilities fitting him for a more elevated situation”. Captain Dubose would have preferred sea command, aiming to rid the waters of pirates and wreckers. Whatever more elevated position might have been his lot, Mr. Dubose at least elevated to the cupola. In under a year since construction began—four days after Dubose landed on the Key according to his meticulously annotated family bible—the Cape Florida Light was first lit on December 17, 1825.

Local lore holds that when the Dubose family, including five kids, moved into the lightkeepers cottage, they became the first American family to assume a full-time residency on Key Biscayne. Mr. and Mrs. Dubose increased the local population, parenting three more children. There is some reason to consider that Mr. Dubose may be the first example of independent and practical thinking in a Key Biscayner. That’s because he had illuminated the light on his own initiative, without communicating first with authorities in Key West, who chastised him for breaching the settled procedure of advance notice. Consistent with what would later become characteristic of the neighborly Key Biscayne ethic, at least one source suggests that he lit the lamps at the request of the construction manager, Mr. Humphreys, who considered that illumination would better assure curing of glazing in the lantern.

Whatever his actual motivation was, the Key West authorities were displeased and Dubose was told to extinguish the light until its presence could be advertised in national newspapers. The result was a “second” first lighting on March 10, 1826.

Although the historical telling of the Dubose family on Key Biscayne has idyllic features, John’s tenure as lightkeeper was troubled. The Collector of Customs in Key West was his immediate supervisor, and the two didn’t get along. Food, supplies and mail from Key West to Cape Florida were slow and unreliable, making life uncomfortable for an isolated settlement on an island wilderness, without neighbors. He requested a boat, which surprisingly, had not been contemplated for an island posting. John wrote a letter to a Mr. Pleasonton, the executive in charge of lighthouses: “… the situation of this light is far different from that of any other on the American coast. There is no one so far removed from a settler’s part of the country… where a keeper has to send so far for his supplies, cut off from all civilized society.” Some months later, he got a boat.

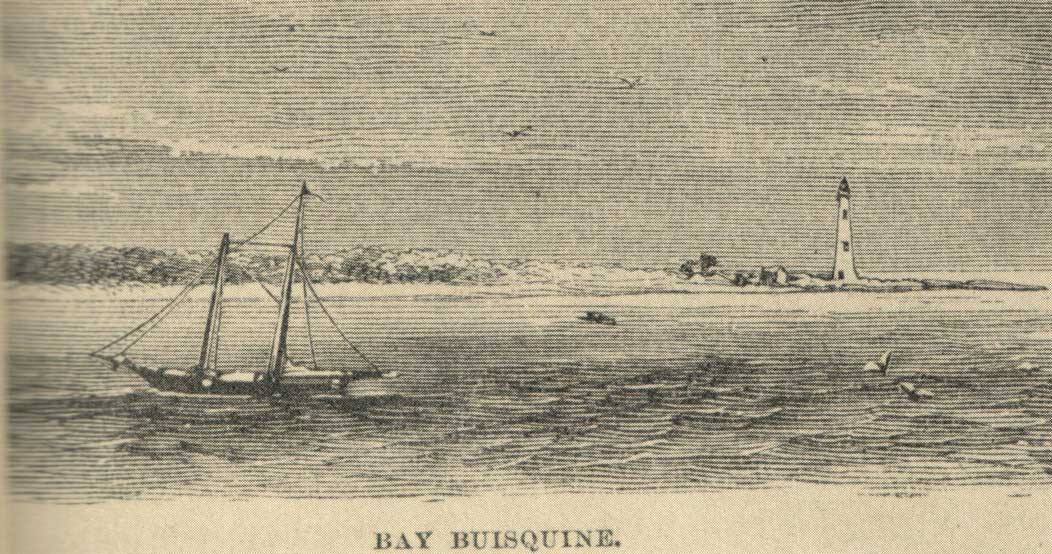

Among his clamor for provisions, John also made startling observations about as-built conditions, noting, among other things, “…this lighthouse appears to be gradually settling and inclining to the East owing, I suppose, to want of sufficient care in fixing the foundations.” Certainly, the 1835 hurricane that created Norris Cut damaged the tower’s foundation and the keeper’s cottage, but apart from storm damage, inspections revealed that the tower’s base was not five feet thick as designed, but hollow. Nevertheless, John’s and his family’s stewardship and hard work both masked and helped shore-up foundational deficiencies. The tower was painted white and gardens adorned the cottage, making a very pleasant scene of “Bay Buisquine” in an early Harper’s Weekly illustration, which of course did not depict swarming mosquitos and the swampy terrain. Guiding countless ships from harm’s way into the shelter of what became known as Hurricane Harbor, the Cape Florida Light marked real improvement.

Under the Dubose stewardship, Key Biscayne was improving. And then, as has happened throughout history and as will happen again and again, outside forces interceded. American history recounts three Seminole wars in the first half of the nineteenth century. For the Seminole peoples, there was one war, provoked by sustained, organized, purposeful harassment and armed attacks beginning in 1812, some five years before Andrew Jackson invaded Seminole Florida. From that time and continuing for nearly a half century, the Indigenous Floridians faced unending threat, aggression and violence. Seminoles and former slaves finding community with them were being herded southward, toward what was known as Key Biscayne Bay. Recurring assaults, a national policy of forced relocation and the myriad of attendant deprivations reinforced animosities. The Seminoles survived, resisted and sometimes hit back.

On December 28, 1835, a military force under the command of Major Francis Dade was ambushed near Ocala, spawning anxieties and reprisals, increasing the already intense cycle of threat and violence. A hint of local tinder comes from a report from John Thompson—one of the lighthouse defenders as we will see—who postulated that a settler named Lumkin killed an elderly native known as Alabama, prompting indigenous reprisals in our area.

Keeper Dubose sent repeated warnings to the military authorities, whose non-responses were similar to those ignoring requests for supplies. In January 1836, one William Cooley of Fort Lauderdale left work for home and found his family murdered. The alarm spread and roughly 60 settlers in the newly formed Dade County sheltered at Cape Florida. Consensus emerged that the island was not the safest place, and they decamped to Key West.

The vulnerable and constantly-provoked Seminoles could certainly see the looming lighthouse from all over. Key Biscayne was an inextricable part of their domain, in their lives and legends. It has been suggested, plausibly, that it would have been highly disturbing for the Seminoles to encounter that arrogant tower installed on their beach—perhaps a spy perch monitoring their movements—with its unnatural light polluting the darkness.

Naval commander Alexander Dallas sailed his Florida Squadron from local waters just as a “most perilous situation” was set to unfold on Key Biscayne. John Dubose had gone to Key West with his family—a consequential decision that would haunt him. He left John W.B. Thompson and his assistant Aaron Carter, a former slave, in charge of the light. At around 4 p.m. on July 23, 1836, 40 to 50 indigenous warriors charged the lighthouse site. Thompson and Carter made it to the tower through a hail of bullets, finding tenuous refuge in the barricaded tower. They fired back from the tower window while their assailants tried to force the latched door. The attack lasted all night. Messrs. Thompson and Carter sawed away the top rung of the wooden staircase, creating a protective gap to deter ascending attackers. But fire as a weapon rendered a direct assault unnecessary. The cottage and out-buildings were ransacked and burned, as was the tower door, sending flames up the shaft. Tins of oil ignited and Thompson and Carter were forced by smoke and heat out of the tower, onto the narrow encircling platform. Thompson was shot six times, three in each foot according to his own after-action report. Carter was killed.

Despite his wounds, Thompson managed to throw a powder keg into the inferno within the tower. The blast and sight of the flames caught the attention of a U.S. vessel, the Motto, thought to be about 7 miles out to sea at the time. Seeing the inferno, the Motto made its way towards the mayhem, and the invaders scattered as boats approached. The operation to rescue the traumatized and exhausted Thompson and recover Carter’s body from a 60 foot perch is a tale in itself. Ingenuity and persistence prevailed and Thompson was able to be lowered safely. Carter’s burnt remains were buried by the lighthouse.

The lighthouse tower withstood the attack, severely damaged however. The Cape Florida attack informed prevailing military thinking that regarded Key West, the Dry Tortugas and Key Biscayne as strategic points, requiring fortification. Meanwhile, in 1842 Congress passed the Armed Immigration Act, intended to pressure Seminoles to emigrate under threat of violence. And while this chapter of American history continued to unfold, still, years passed before the lighthouse was rebuilt. The story of the reconstruction might remind some of modern-day scandals, replete with bilking the government. Finally, after 11 years, the Cape Florida light was re-lit during the night of April 30, 1847, atop a new tower 65 feet tall, 24 feet diameter at the base tapering to 12 feet at the top, with thick walls and a deeply laid foundation.

The tower’s greater height and the more vivid Fresnel luminosity helped. But ultimately, commitment to the on-shore lighthouse at Cape Florida, drawing sea captains so close to the reefs they were so desperate to avoid, gave way to the recognition that safety would be better served by an off-shore light.

Fowey Rocks Light lit in 1878, and Cape Florida Light became obsolete. Abandoned by the federal government, the lighthouse facility was sold as surplus property. Almost a century later, the State of Florida acquired the property in connection with the establishment of Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park, which opened January 1, 1967. On July 4, 1974, the Coast Guard reactivated the light. It remains lit today as a Coast Guard registered Private Aid to Navigation.

The tower and cottage have garnered justified tender loving care over the years. The cottage today is a replica of the original, built in the 1960s. The metal cupola atop the tower was replaced in 1996 using the original 1855 plans. The facilities were substantially renovated in 1992, in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew.

There are 96 flat triangular windows in the lantern room, which was designed by General Meade. Flat windows set at a 90-degree angle to the lens augment the light visible at sea. The diagonal window frames—a new feature in American lighthouses in 1855—ensure that light is evenly distributed around the horizon.

Seeking new members from across the Key!

Whether you are a Key Biscayne history novice or savant or just want to learn more about our unique history and be involved in a worthwhile civic endeavor, all are welcome! KBHHS is an all-volunteer organization with numerous opportunities for participation, leadership roles and initiatives and community involvement.

Where the Past is always Present KBHistory.org

Please join us. All goals are more easily achieved and better realized with broad participation. Help with the KBHHS Mission and have fun in the process.